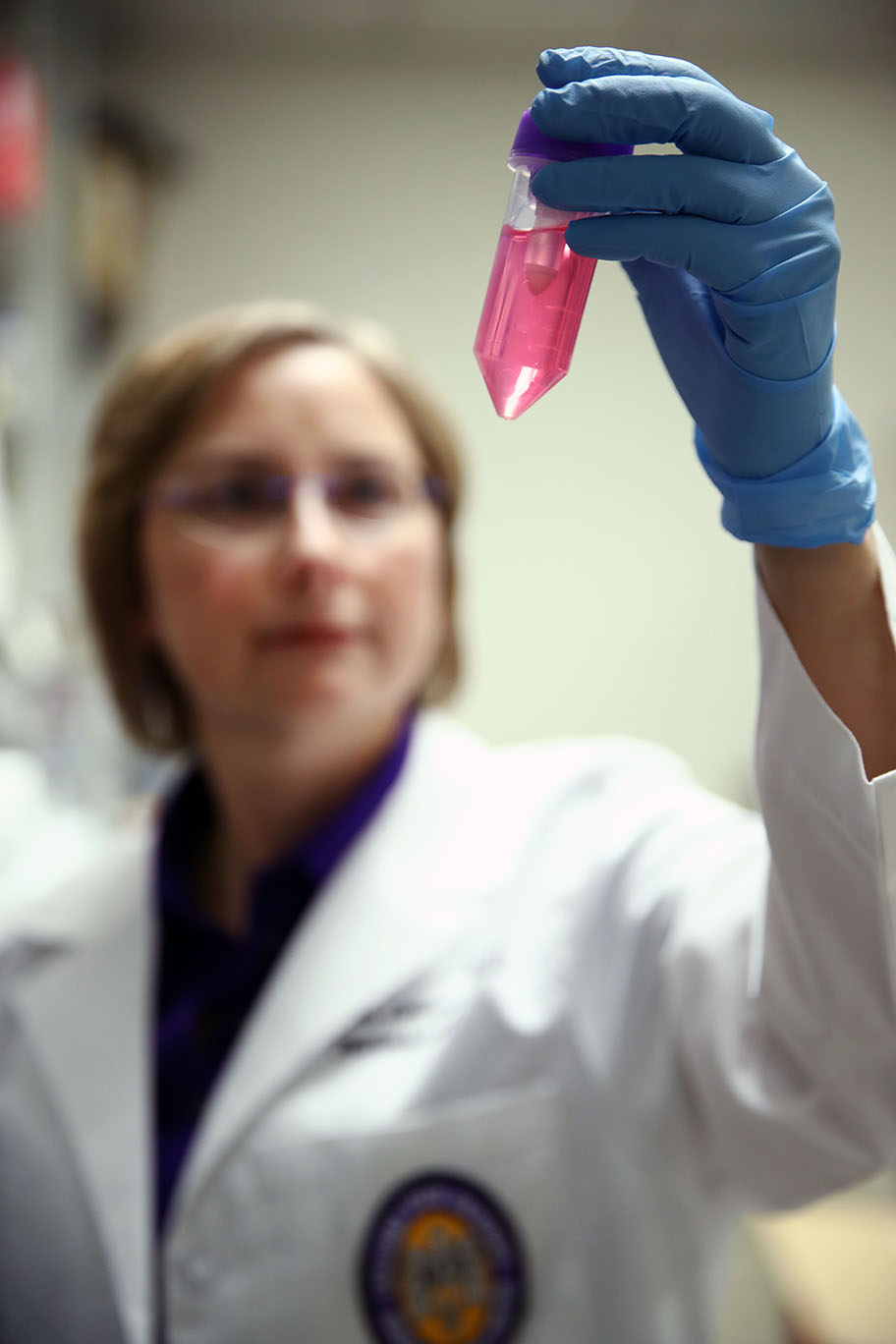

Dr. Stephania Cormier holding up a tube of dissociated cells from the lungs. Photo Credit: LSU College of Science

As a young woman, Stephania Cormier loved sports, especially basketball. She started as a center—a head above her peers in sixth grade. She ended as a guard—a head below as a high schooler. But throughout, she had difficulty competing because she couldn’t stop coughing. Her end game: sidelined, frustrated and huffing into a paper bag.

“Back then, asthma wasn’t adequately diagnosed,” she said. “Doctors put people on antibiotics with all of their side effects.”

Cormier had to wait for relief until college, when she visited a pulmonologist in Lafayette. He prescribed an inhaler, the first medication that actually addressed the symptoms of her newly diagnosed disease: asthma.

Fast forward to today, Cormier is the Wiener Chair in LSU’s Department of Biological Sciences where she heads up a portfolio of biomedical research that scrutinizes asthma’s non-genetic causes and looks ahead to potential cures. Cormier is also a professor of comparative biomedical sciences at the LSU School of Veterinary Medicine.

“Asthma is controlled and controllable right now, but we can’t get rid of it,” she said. “I want to know how it happens. If we know that, then we can stop it.”

The breathless search

The shortness of breath associated with asthma attacks happens because airways have swelled and constricted. If you have a family history of asthma, you have a greater risk of developing the disease. That’s the genetic risk.

However, lung tissue damage as a result of pollution or illness plays a factor in many asthma cases. That’s where Cormier focuses:

What causes asthma besides genetics?

Cormier and her team of researchers probe the role of epithelial tissue damage due to respiratory viruses and pollutants. Epithelial tissue includes cilia, the hair-like structures that sweep away harmful particles. When this tissue and the cilia become damaged, the body’s exposure to harmful disease—specifically asthma—increases.

Triggers for an attack can vary widely, ranging from cold air and physical activity to food allergies and airborne irritants. While asthma currently has no cure, both maintenance medications and “rescue inhalers” can control the frequency of asthma attacks.

Baby’s breath

While her personal diagnosis certainly adds a sense of urgency for her current research, Cormier didn’t originally plan to delve into the asthma field. Her post-doctoral fellowship at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona centered on a staff physician’s project with chondrocytes, the cells found in cartilage tissue. However, when that researcher left Mayo, she had to find another sponsor. Luck, fate—or whatever you want to call it—intervened.

“The guy across the hall was working on asthma,” she laughed, explaining how she suddenly switched to a new, but familiar, research path.

With her new supervisor across the hall, she studied the history of respiratory syncytial virus, known as RSV, and its links to asthma. Cormier learned about the tragic history of a 1960s vaccination trial against RSV that resulted in the hospitalization of 80 percent of participants and the death of two babies.

Where others saw a failure in the chemistry of the vaccine, she saw an opportunity to re-examine the vaccine recipients.

“They were studying the wrong models,” she said, referring to that vaccine’s development based on the way an adult body functions and responds to illness. “You can’t study an infant

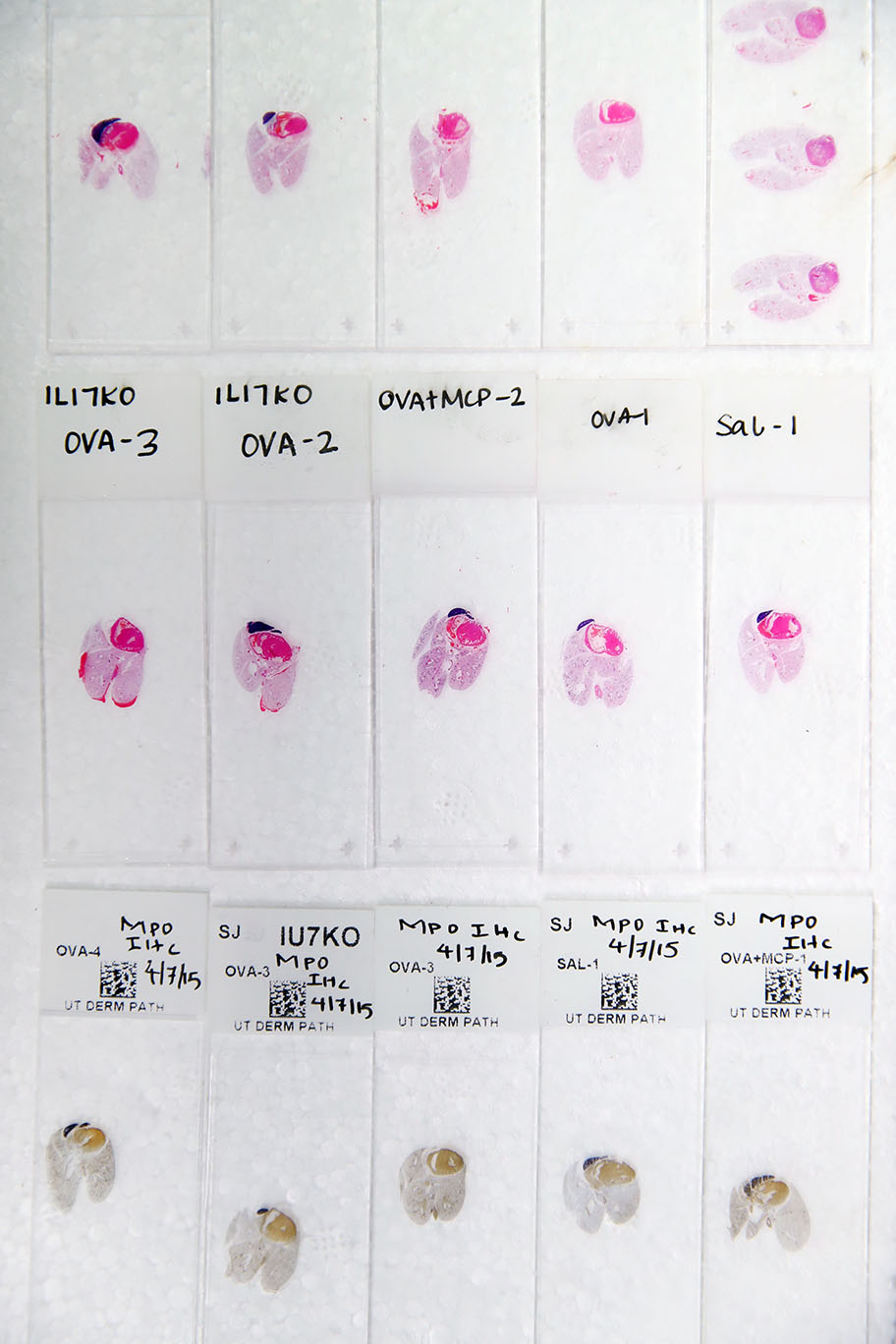

Histology slides to test for airways disease.

Photo Credit: LSU College of Science

disease in an adult. Infants are not fully developed. They’re so susceptible.”

Since then, her collaborations with scientists across LSU and at the University of Tennessee Health Center have uncovered the reasons why assaults on the infant immune and lung systems because of RSV and pollution often have lifelong health effects.

Her exploration of pollution includes joint research projects conducted through LSU’s Superfund Research Center, where she serves as director. The center focuses on how environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFRs)—the pollutant particles found in hazardous waste cleanup or containment sites—form and how to mitigate their impact.

“Our research supports a greater understanding of the relationship between lung health and pollution. Outside of the world of science it pushes regulations that aim to reform the environmental impact of polluting industries,” said biological sciences major Felix Harrison, an LSU student who serves as a research assistant in Cormier’s lab.

Hold your breath?

While Cormier and her team search for the vaccines and medications that will cure the non-genetic causes of asthma, there are several ways that average people can reduce their risk.

Research has found that infants are less likely to get sick if they are breastfed and if their caregivers wash hands frequently. The microbiomes passed from mother to child via vaginal delivery also help to protect babies.

To avoid EPFRs, stay away from major roadways and other known sources of pollution. You should also wear a mask on high-pollution days. The good news is that the Louisiana diet—blueberries, pecans, red beans—is rich with antioxidants, which protect against pollution’s damage. “Red beans and rice on Mondays. So far that’s the best we can do,” Cormier said. Her lab is examining how to isolate the protective antioxidant properties found in these foods to create medicinal supplements that can make a difference.

Breathe easier

According to data from the University of Chicago’s Energy Policy Institute, the average human would live 2.6 years more if deadly pollutants were eradicated. In the United States, the average resident loses less than 1 year of life to pollution. But scientists like Cormier seek ways to bring that number to 0.

“Research work is a long, time-consuming process, and you naturally want results as soon as you can get them,” said biological science major Alexander Scotty, another LSU student who works with Cormier. “It’s rarely that simple, and you have to hope you can find a piece of the puzzle that will make it easier for yourself—or someone else—in the future.”